Sean Ellenby watched as Oakland University basketball player Jack Gohlke sunk yet another three-pointer during the first round of the 2024 NCAA March Madness Tournament.

Ellenby, a marketing director at apparel decorator Campus Ink, fired off an Instagram DM to Gohlke as his colleague sat next to him at the bar, developing a tentative merch design to commemorate the explosive performance that allowed for 14-seeded Oakland’s upset over the University of Kentucky.

Less than 24 hours later, Gohlke’s merch was available for purchase on the NIL Store, the branch of Campus Ink that sells merch capitalizing on college athletes’ name, image and likeness (NIL) – and gets those athletes paid for it.

In 2021, the NCAA reversed its long-standing policy that student athletes couldn’t make money from the commercial use of their NIL, opening the doors for the now billion-dollar NIL industry.

But now, there’s another NCAA settlement on the horizon that will likely allow schools to directly compensate athletes – changing the landscape of college athletics and NIL yet again.

With that comes big potential to expand the NIL branded merchandise market, as smaller schools will have to fight even harder to compete with the biggest names in college athletics, said Noah Henderson, the director of sport management at Loyola University Chicago.

“It’s just going to become even more important [for schools] to do everything they can for the student athlete to make sure that their total NIL package is big enough to make it worth their while,” Henderson said.

What’s Going on With the NCAA?

In late July, the NCAA and the power conferences (the biggest in college football) agreed to a settlement to resolve a set of anti-trust lawsuits related to athletes denied the right to earn off NIL prior to 2021.

A piece of the settlement that’s especially relevant to the future of college sports is a “revenue-sharing model,” in which schools will be able to pay student athletes using a set percentage of the athletic department’s revenue.

“This basically means that, for the first time ever, institutions will be able to directly pay their athletes,” Henderson said.

The settlement still has to be approved by the courts, which could take months.

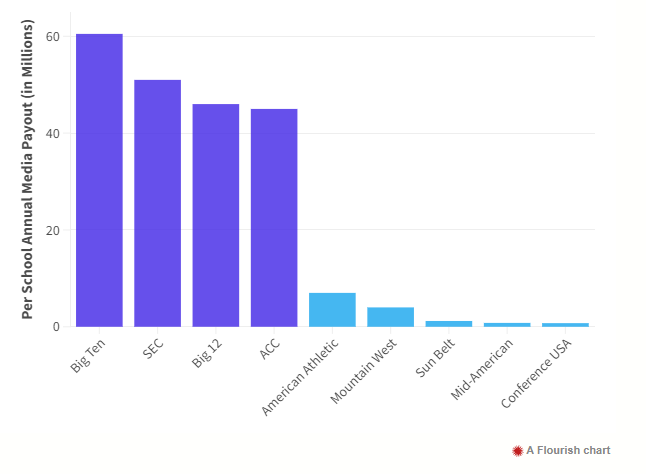

However, if it goes through, it’s a model that heavily favors the power conferences because of the size of their audiences – and media deals. On average, schools in the Big Ten Conference, for example, received more than $60 million annually through deals with TV networks last year. That’s not counting additional payouts for events like the College Football Playoffs or March Madness Tournament.

By comparison, the entire American Athletic Conference – which includes schools like the University of South Florida and the Naval Academy – makes just about $83 million per year in media deals, amounting to an average of $7 million per school annually.

The Power Four, Henderson said, will have an even bigger advantage in recruiting moving forward because of the large amount of money they’ll be able to offer athletes.

As such, other schools are going to have to get creative to compete with that type of income.

Developing a strong infrastructure for athletes to easily sell merchandise could be one way to do that, both as a factor in decisions for potential new recruits and to prevent the Power Four from tempting athletes off their rosters through the transfer portal, said Bill Carter, who runs the NIL consulting firm Student Athlete Investments.

“They have to get their student athletes NIL income beyond what they might make through the settlement,” Carter said. “They need to really become dealmakers.”

Even at smaller institutions, there is a vast market for merchandise among fans, said Ellenby.

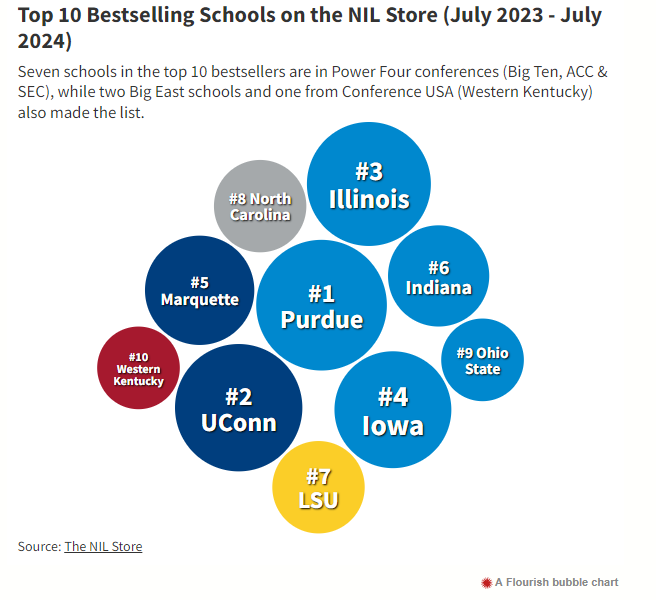

Western Kentucky University, for example, advertises players’ NIL Store pages on the jumbotron at games and with QR codes at signing events, Ellenby said. Despite not being in a power conference, Western Kentucky rounded out the top 10 bestselling schools on the NIL Store site this year – above big athletic names like Penn State University or the University of Florida.

“They’re not going to have that same big stage opportunity as some of those bigger schools,” Ellenby said. “But they are going to get their local community excited, and they’re going to back their players and get them excited as well.”

State of the NIL Merch Market

The NIL Store has paid out more than $1 million in royalties to its athletes over the years, as has NIL retailer Influxer, which boasts more than 17,000 active athletes on its site. The market goes beyond just apparel; collegiate trading card company ONIT Athlete reported more than $1.6 million in royalty payments last fall.

Even so, merchandise is far from the largest segment of the NIL market. Instead, social media, brand deals and collectives – shell companies that funnel large amounts of money from wealthy university donors to athletes in exchange for (often token) NIL engagements – all dominate the market.

Promo pros have been hesitant about the NIL market in the past, mostly because of concerns about licensing. Most NIL merch is co-branded with both the athlete’s name and their university’s, so licensing can be complex, especially because there isn’t a standardized way to get licensing for all schools in a conference or all athletes at a school.

The license the NIL Store uses, Ellenby said, allows a product to be co-branded with the university logo, but it must also include a specific athlete’s name, image or other identifying criteria.

However, Carter said, the schools aren’t the ones that need the brand recognition or the revenue from NIL licensing deals. Instead, it’s about the athletes.

“It’s less of a revenue-generating operation for the schools themselves and more of a revenue-generating operation for the athletes in this case,” Henderson said. “Because their goal is, once again, to create that attractive NIL package.”

Supporting Female Athletes and ‘Non-Revenue’ Sports

Because of the existing demand for university-branded merchandise, individual athletes already have a market for their merch, said Thilo Kunkel, an associate professor in marketing and sport management at Temple University.

“The university may be the key driver or the athlete may be the key driver, but it’s that duality of involvement that can come and help the athletes sell merchandise,” Kunkel said.

What the athletes get in return for those sales can vary wildly.

Athleticwear retailer Fanatics has been reported to only offer about 4% royalties to its NIL athletes, compared to the NIL Store’s reported 20-30%. That usually amounts to about $6 to $15 in royalties per product sold, Ellenby said, depending on if it’s a T-shirt or a more expensive item like a jersey.

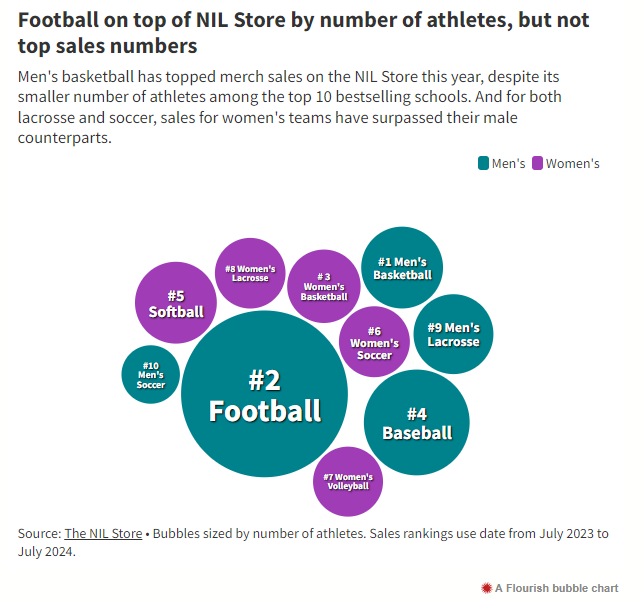

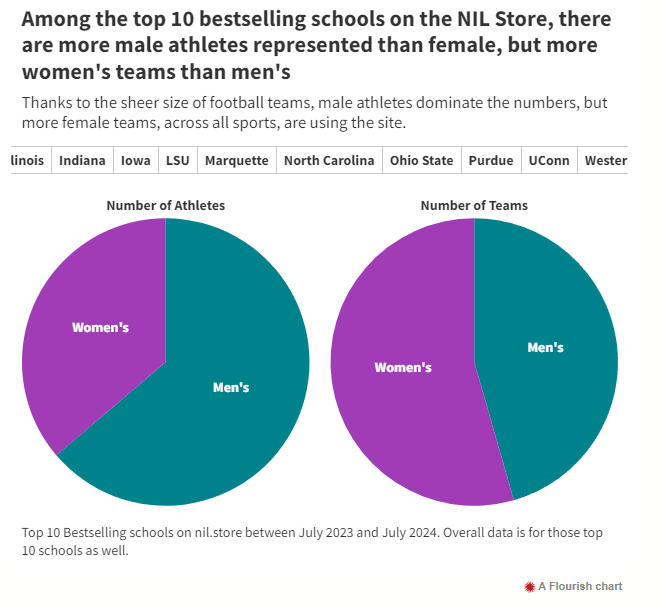

The NIL Store’s products lean a bit pricier because of that – ranging from an average of $40 for a T-shirt to above $100 for jerseys. Prices, though, are comparable for both men’s and women’s teams, and Ellenby said women’s sports sell almost as well as men’s do – if not better, in the case of lacrosse and soccer.

That reflects increasing demand for women’s sports merchandise industry-wide. Fanatics sold more Caitlyn Clark merchandise in the 24 hours after the former Iowa women’s basketball superstar broke the NCAA scoring record in February than any other individual NIL athlete (male or female) has in total since 2022.

“All of these female athletes are more in the spotlight than ever because NIL allows them to be,” said Henderson.

Opportunities for Promo Growth

Kunkel said he expects to see more products like personalized equipment or signature shoes emerge as athletes continue to partner with brands. That doesn’t automatically translate to NIL dollars in athletes’ pockets, but it could if student athletes can find ways to commercialize.

Merch that capitalizes on viral moments can also be an effective way to generate more NIL value for athletes, Ellenby said. The NIL Store worked with Purdue during the March Madness Tournament, for example, to ensure that the athletes got a cut of tournament merchandise sales, even though the products weren’t associated with any one player.

Despite its potential, though, the marketing problem with conglomerates like the NIL Store, says Carter, is that they’re not the first place people look to buy college athletics merchandise. That would be college bookstores, which typically wouldn’t have the inventory space to support all of a school’s athletes interested in pursuing NIL.

The NIL Store does pop-ups for the schools located near Campus Ink’s headquarters in Urbana, IL. They’re also working on pioneering a “blanks” program, which would provide college bookstores with a heat press, along with blank T-shirts and decals for participating athletes. The decals would be heat-sealed on demand to help support more athletes while not taking up as much inventory space with physical product.

Still, as more schools turn to internalizing NIL proceedings with strategy units or on-campus merch stores, Carter thinks there’s opportunity for “mom and pop” distributors, especially those who specialize in products other than apparel, to get in on the action.

Some schools might be locked into licensed apparel deals with retailers like Nike or Under Armour for athletics apparel, he said, but there’s space for creativity if the industry wants to bring other types of products to the table.

And as with any industry, the value of NIL-branded merchandise goes further than just those royalty dollars.

“When a fan or a family member or a friend purchases an athlete’s product, that’s just the start,” Ellenby said. “It’s really a vehicle for marketing for yourself. Now that fan is going to be out there in the community, in the streets, wearing your merch with your name on it, and they’re marketing for you.”